Galleria Maggiore, opened in 1978 in Bologna—where its main headquarters still are—and active in the field of early 20th-century art, is going through a double transition: a general one, marked by the globalization of the art market, which calls for new strategies; and a generational one, through the involvement, alongside Franco Calarota (owner with his wife Roberta), of their daughter Alessia, born in the same year the gallery was founded. We met father and daughter on their return from The Armory Show in New York (the gallerist has joined the fair’s organizing committee) and just before their departure for Art Hong Kong.

Franco Calarota, when we scheduled this interview, you said: “This is the right moment because I’ve just come back from New York.” Why?

F.C. Because that experience really makes the differences between Italy and foreign countries apparent when it comes to the art market. Italy: imagine a professional with a good income who pays taxes and decides to buy an artwork of a certain value—say one million euros—from a gallery. I, the dealer, have to explain that there is 21% VAT to pay and a 4% resale right. After that, I must identify the buyer through his tax code; then comes the payment, and he has to make a bank transfer. Then comes the declaration—actually, it would be more accurate to call it a “report”—to the Revenue Agency. Quite likely, after such a purchase, he will be contacted by the Agency for a check or at least an explanation. New York: a similar tax-paying professional passionate about art who buys the same type of work might have a plaque placed in a museum in his honor and will receive recognition. That is the difference. It’s clear that with VAT at 5.5%, as in France, everything becomes easier, and only in Italy is someone who buys an important work looked at with suspicion. Ours is a country that penalizes investment in art.

Allow me to rub salt in the wound: you work in a sector—historical modernism—in which the system of export notifications applies.

F.C. I’m not saying there should be no oversight by the competent Ministry. But why is everything so much simpler in France? If the State identifies a work of national interest, it has two years to find the funds to purchase it. Once that deadline passes, the work is free and can be exported. Here instead, the work gets flagged regardless of whether there is any actual interest.

And do you have a solution?

F.C. When Giovanna Melandri was Minister of Culture, I proposed this: for each artist, identify the 100 works that absolutely must not leave Italy and immediately subject them to notification. All the others should be free.

Speaking of ministers: Urbani, though elected in a liberal-leaning government, once said the art market is full of “nonsense.” Do you think Italian gallerists are qualified enough to reject such insinuations?

F.C. Unfortunately, not all of them are.

A.C. Let’s say there’s a kind of natural selection: those who truly do quality work rise to the top, even though Italy is a very polarized country, and even within the system there are gallerists who are highly regarded in Italy but unknown abroad. They may have the right connection to get into one fair, but that’s all—they have no other room to move.

F.C. I’ll add, speaking of natural selection, that it’s no coincidence that in 2009 the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris asked for our collaboration on the Italian section of De Chirico’s first complete Paris retrospective. And now, strengthened by our international credibility, we’re presenting our Morandi's works at Art Hong Kong.

Is this your first time in Hong Kong?

A.C. Yes, although we already have important Chinese collectors. Our work has become a reference point for Morandi’s oeuvre internationally—even in the East.

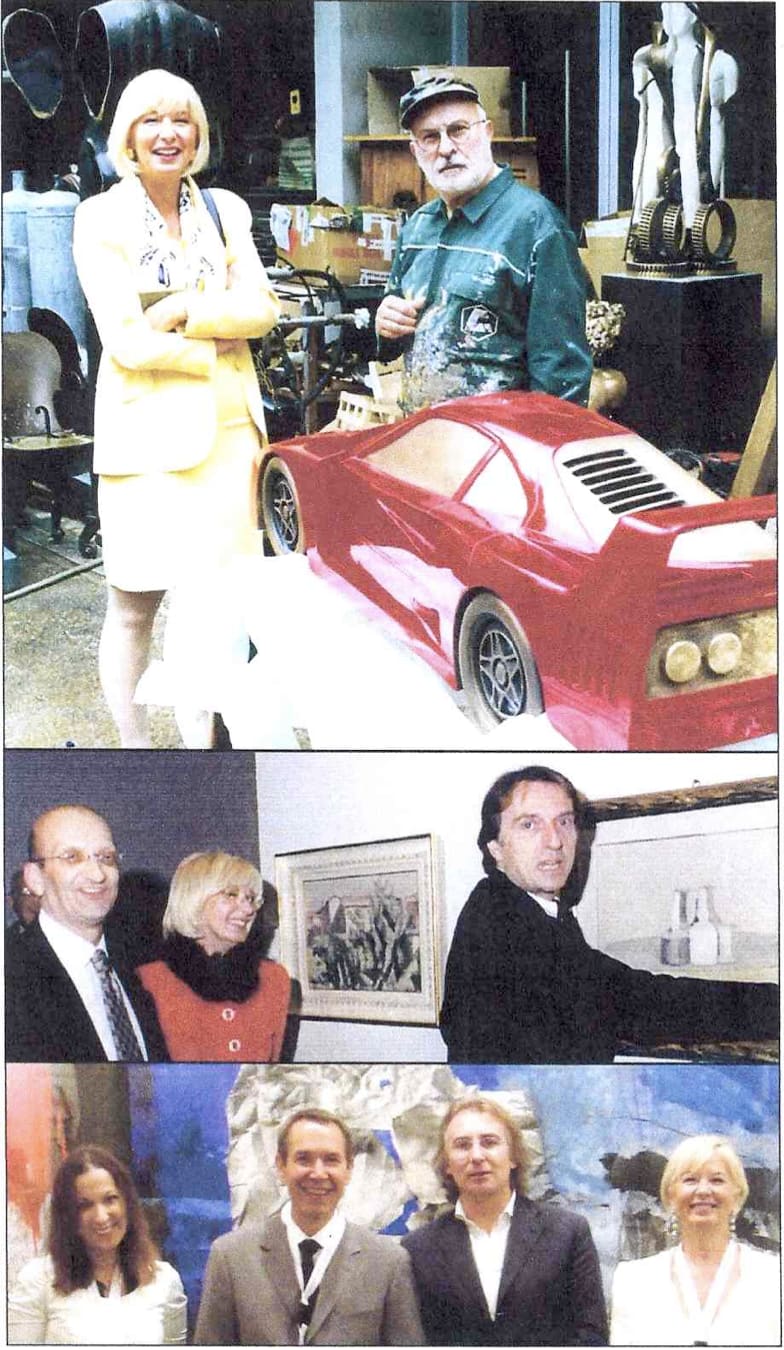

From the top: Roberta Calarota with Arman, author of the monument dedicated to Ferrari, made in 1999 and commissionated by the Maggiore; Luca Cordero di Montezemolo in the Galleria's stand at ArteFiera, Bologna, where he mimic the theft of a Morandi; Jeff Koons with Alessia and Roberta Calarota and Emmanuel Clavé at Abu Dhabi Art in 2009.

Why don’t you participate in ArteFiera in your own city anymore?

F.C. For years we’ve been working with foreign collectors and museums. So we’ve considered our participation in ArteFiera unnecessary. But above all, if I decide to participate in the Bologna fair, I must do it at my best, “burning” material that is precious to me for other occasions. Regarding other issues about ArteFiera, I’d rather not comment.

You’re not even members of the national trade association…

A.C. In my opinion, that association doesn’t make much sense—but that’s me speaking, Alessia Calarota.

F.C. I didn’t renew my membership because at a certain point I realized the association wasn’t fighting for issues truly useful to the category—like tax benefits, taxation, and so on.

Why, compared to many of your colleagues who dislike fairs because they threaten the traditional role of the gallery, are you strong supporters of them?

A.C. Globalization means fairs are springing up everywhere. So on the one hand, I agree with colleagues who oppose the fair system; on the other, I think this spread is a positive sign because it means there is growing demand—and this fuels the dynamism that also brings encounters with different cultures and countries.

F.C. The role of the traditional gallery includes educating the collector’s taste, as well as mediating between the market, the artist, and the collector. It’s clear the number of fairs, their quality, and their format need to be reassessed. To be clear: they are not curatorial exhibitions. There is a risk here. That’s what museums or biennials are for.

What do you think of online fairs?

F.C. We’ve never taken part, but I understand that one must pay some attention because it’s an important medium. Still, I believe online art doesn’t have a great future because it lacks the emotional component that, in my view, is essential for engaging a collector.

A colleague of yours recently complained that buyers increasingly arrive loaded with information—prices, statistics, typologies—downloaded from the internet, data not always compared with different market realities, which further reduces the gallerist’s role. Does this widespread access to information harm you or help you?

F.C. It neither harms nor helps us. That is the role of auction houses, which intervene only on the market level: like the stock market, the auction house is the intermediary that sells a work at a given price when its value rises.

Do auction houses irritate you?

F.C. In the past, auction houses did not produce catalogues like today’s. They were lists with lot descriptions, almost without illustrations. Illustrations weren’t needed because they didn’t have to persuade the buyer—the buyer was an expert, an insider. Today auction catalogues boast beautiful illustrations and come with critical notes that influence the market. This is the real damage to the market. The auction house should stick to its job: sourcing material and selling it. But this is no longer the case. And why? Because of the lack of professionalism among gallerists—not only in Italy, but worldwide. I won’t name names, but now you need to tell me how many gallerists in the world have passion, competence—who, when they sell a work, speak about its meaning and historical-cultural value. People mostly talk about numbers, market, speculation, investment, fashion, or other reasons. That’s the real problem; it’s clear that in this system, the auction house has had easy ground to step in. Auction houses, financially powerful structures, claim to work in support of collectors, acting as consultants when connecting sellers and buyers. Instead, auction houses—and this would require a long chapter—produce big market movements, big speculation, and big influence. Influence that’s unsuspected because it is public.

A.C. I think the opposite: I’m pro-internet, pro-auction houses, pro-Google, because I believe we’re going through a phase that has never happened before. It’s true that auction sales make headlines and create “events,” but the good thing is that this news factor attracts wealthy individuals who previously had no interest in art.

The Calarotas at Mostra Internazionale d'Arte Cinematografica di Venezia.

How does one join the Armory Show committee?

F.C. They reached out to us.

And how did the fair go?

F.C. It always goes well for us. The Armory Show’s audience consists of real collectors. Interesting encounters happen, such as one that helped organize an exhibition at the Morgan Library pairing Philip Guston with Morandi’s drawings and engravings.

In fair committees, gallerists are asked to judge the work of their colleagues. Doesn’t this create conflicts of interest?

F.C. Gallerists are the most qualified for the task. But yes, if you’re not careful, risks exist. In forming committees, one should use the same criterion I would apply to export notifications: identify the 100 most important gallerists in the world and involve them in rotation. I believe each gallery should be responsible for what it presents and exhibits; the committees’ duty, instead, is to assess authenticity—an issue especially for modern art—and, in contemporary art, the solidity of the artists, who should not be amateurs thrown into the fray. But I repeat: no gallerist on a committee has the right to impose choices or prevent a colleague from exhibiting works by a particular artist just because that artist is also represented in another booth.

What is your relationship with artists’ heirs?

F.C. Since the death of Mattia Moreni, we’ve worked with the archive dedicated to him: the complete catalogue raisonné is about to be published. The artist’s widow is extraordinary: extremely knowledgeable and a boundless source of information. We also manage Leoncillo’s archive, but that is extremely complicated, because recovering this artist’s works—the greatest informal sculptor in Italy—is very difficult. Those who collected Leoncillo did so with true passion and are therefore not very willing to lend works. But if your question refers to the kind of relationships one can have with heirs, aside from the cases mentioned, sometimes interests arise that can hinder the gallery’s work.

Let’s talk about the future of Galleria Maggiore.

F.C. My ambition is to continue operating actively within the art system: I want to do my job as a gallerist at my best, but also have more time to cultivate relationships with institutions and develop new projects and ideas. Alessia will increasingly handle the contemporary side.

A.C. Yes, I’d like to “open more” to the international contemporary scene through living artists. I’m not talking about primary market representation, because I don’t see myself as a talent scout. I’m building an international team to work with me: today you can no longer be just Italian—you must be many things.

You divide your time between Italy and Paris: are you thinking of opening a space there as Tornabuoni did?

A.C. Yes, we’re working on that, though not only in Paris.

F.C. They won’t be large galleries, but small spaces conceived as showrooms in major cities such as Paris, London, and New York.

A.C. In Paris we already have a space called Advisory Office where we meet collectors, but I strongly believe in emerging countries: I now see the world in its entirety, not just the West.

Franco Calarota, list three works from your collection that you would never part with.

Three are too few… Let’s say, a 1950 Franz Kline, a Fontana, and a Campigli—but also a Morandi… No, three are too few.

From the top: Franco Calarota with Takashi Murakami; with his wife and Joseph Kosuth; the gallerists with Sandro Chia (the first one from the right) and his son Filippo at the vernissage of his recent personal exhibition at Galleria d'Arte Maggiore; The Calarota with, in the centre, Poupy Prath Moreni and Alessandro Bergonzoni at the opening of Mattia Moreni's solo exhibition in 2005.