The Influence of Nietzsche

Although one tends to remember Giorgio de Chirico’s early works—so striking and dazzling—the rest of his life and oeuvre are far less known. The enormous Parisian exhibition seeks precisely to rehabilitate this overlooked corpus. Paintings, of course, with prestigious loans, but also sculptures, drawings, and archives—together forming an almost exhaustive portrait.

His life began under the sign of antiquity and the call of travel. Born in Greece to Italian parents, De Chirico was deeply shaped by the classical education he received in Athens, strongly imbued with mythology. His birthplace was, in fact, the departure point of the voyage of the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece. When he moved with his mother and brother to Munich, De Chirico entered the Academy of Fine Arts and enthusiastically discovered German Romantic culture. But the decisive influence on him was the philosophy of Nietzsche. Very quickly, the nostalgic and symbolist painting of the Swiss Arnold Böcklin merged with the philosophical inspirations of the author of Ecce Homo and Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

The Support of Apollinaire

In 1911, his arrival in Paris played a crucial role at a moment when a large part of his pictorial vocabulary was already well defined, nourished by his first two cultural lives. A first exhibition of three paintings at the Salon d’Automne in 1912 was followed by a presentation at the Salon des Indépendants. De Chirico’s name began circulating, especially in 1913 when he showed thirty paintings in his studio.

He quickly formed a bond with Guillaume Apollinaire. The poet wrote of him: “The art of this young painter is an interior and cerebral art that has no relation with that of the artists who have emerged in recent years. It derives neither from Matisse nor from Picasso; it does not come from the Impressionists. This originality is sufficiently new that it deserves to be noted.” His visual enigmas, with their dry and sharp style, stood out strikingly in an artistic scene dominated by Cubists and by the confrontational energy of the Italian Futurists.

After the outbreak of war in 1915, De Chirico and his brother (known under the pseudonym Alberto Savinio) returned to Italy. He was mobilized in Ferrara. His canvases became emptier, overwhelmed by a heavy and silent solitude; the symbolic network became increasingly “esoteric.” His painting gradually withdrew from Nietzschean influence. It was also in Ferrara that he defined the “Metaphysical” concept of his painting. In this same eastern Italian city, he met Carlo Carrà, a former Futurist who quickly adopted this new approach. Then the rupture in this historical thread came abruptly.

Giorgio De Chirico, Piazza d'Italia, 1962, oil on canvas, 40 x 5O cm, Private Collection, Courtesy Galleria d'Arte Maggiore, Bologne

De Chirico and the Old Masters

Between 1920 and 1935, Giorgio de Chirico declared himself pictor optimus and cultivated a frank classicism. Studying the great masters of painting allowed him to claim a prestigious lineage. Whether posing in costume or drawing inspiration from the compositions of tutelary figures such as Lorenzo Lotto, Michelangelo, Titian, Rubens, Fragonard, or Courbet, De Chirico stood out sharply in the contemporary artistic landscape.

A solitary figure, he did not succumb to the sirens of originality. In the 1940s, his works became marked by seriality and by intense reflection on the value of repetition. This is precisely what would later fascinate Andy Warhol, himself known for his series. The American artist even went so far as to rework some of De Chirico’s works, including The Disquieting Muses, Italian Square with Ariadne, and Hector and Andromache, in one of his 1982 silkscreen series.

The Painter with Two Faces

But how should one think about and understand Giorgio de Chirico’s later works, when he embraced a certain sense of kitsch? How can one resist the temptation to view these canvases only through the lens of curiosity for a reactionary decadence? The art critic Elisabeth Wetterwald attempts to answer in a catalogue essay aptly titled: “What if the late was too early?” She writes: “According to numerous critical texts, De Chirico’s career is divided into two parts: the ‘good’ and the ‘bad,’ the early and the late—approximately 1911–1918 and 1919–1978… Modern art history would thus have retained only seven years from the career of a painter who worked for sixty-seven.”

This delicate undertaking is precisely what the Parisian institution intends to address. “Young artists recognize him as a precursor of postmodernism. His work is being reread: it is the very example of the negation of originality, of uniqueness. De Chirico fought against the simplistic and binary oppositions imposed by modernity; he is an appropriationist before his time…” Wetterwald continues. This final chapter of the exhibition thus explains the relevance of the œuvre of a life so disconcerting, born of a resolutely contemporary mind.

Biograph:

1888 Born in Greece.

1900 Drawing and painting classes in Athens.

1906 In Munich, he reads Nietzsche and Schopenhauer.

1909 First Metaphysical paintings in Milan.

1912 In Paris, meets Apollinaire and Picasso.

1915 With Carrà, founds the Metaphysical Painting movement.

1916 André Breton discovers The Child’s Brain by De Chirico and buys the painting.

1928 The Surrealists finally turn their backs on him.

1929 The artist also devotes himself to writing.

1945 In painting, a return to a kind of pastiche of classical art.

1945–1978 Exhibitions in Europe, the United States, and Japan.

1978 Dies in Rome.

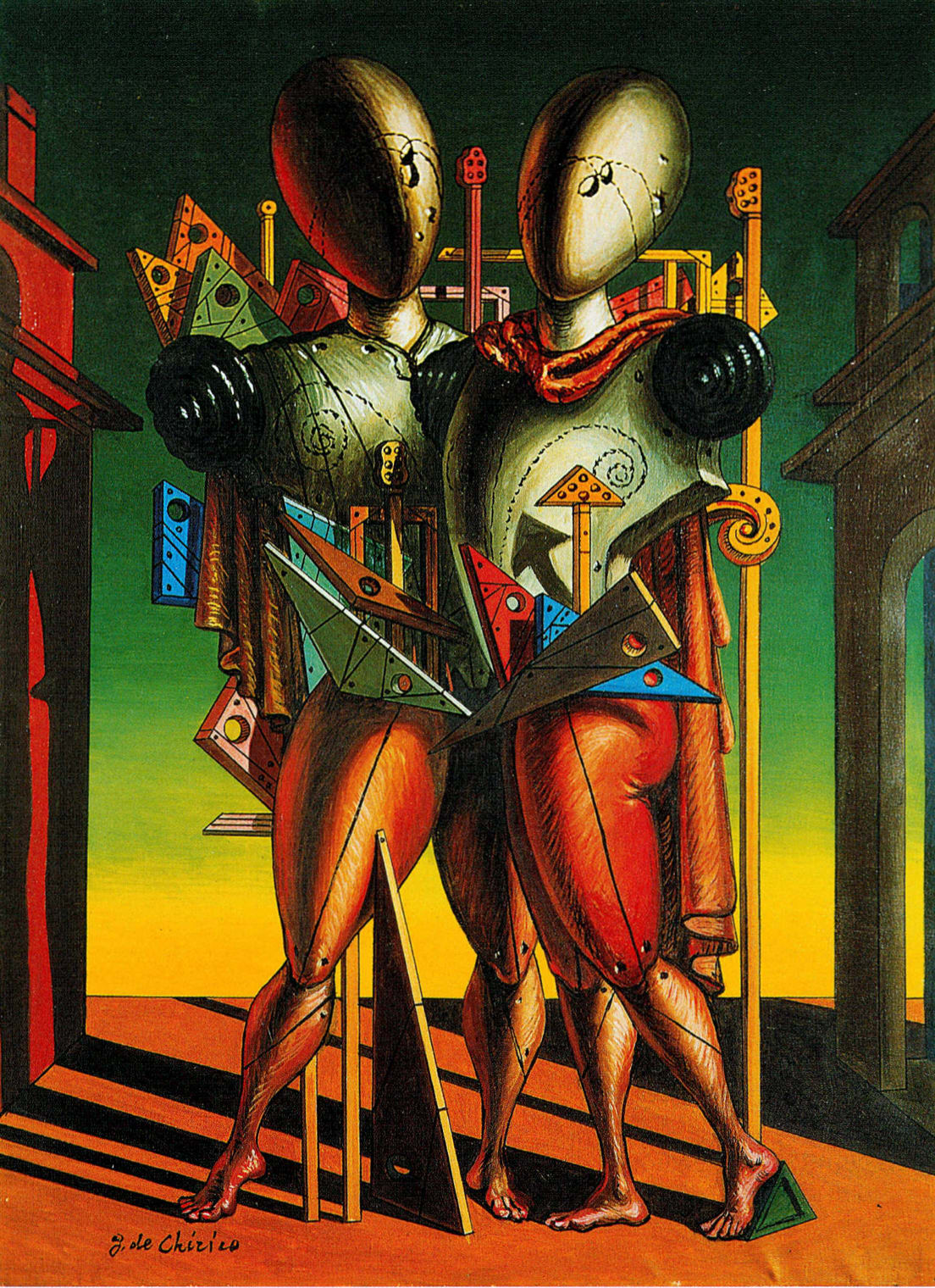

Giorgio De Chirico, Ettore e Andromaca, 1942, oil on canvas, 80 x 60 cm, Private Collection, Courtesy Galleria d'Arte Maggiore, Bologne