This is the realm of “classical contemporary art”, or, if you prefer, “historicized contemporary art”. It is this world—briefly colonized by anti-conceptual and citation-based movements such as Transavanguardia and Neo-Expressionism—that is the focus of the research behind the list of 100 names published here. It follows the list from the previous issue of Il Giornale dell'Arte, which focused instead on “Contemporary 2.0”, the protagonists of more recent, younger art.

The idea for this second installment stems from a basic observation: the contemporary art system is split into two "planets"—that of the recent past, and that of the present. One will notice how artists who established themselves in the recent past are still not only highly valued on the market, but also, from a poetic point of view, incredibly relevant (just to name one: Giovanni Anselmo). These artists continue to be represented by top-tier galleries. Yet the rules and the ecological functioning of these two planets are deeply different, especially when it comes to what defines their respective “seasons”: the market (setting aside, however central, the role of criticism).

There are also figures who manage to operate in both worlds: the so-called “interplanetary” or cross-boundary figures, already featured in the first edition of Power 100 Italia, and mentioned again separately here.

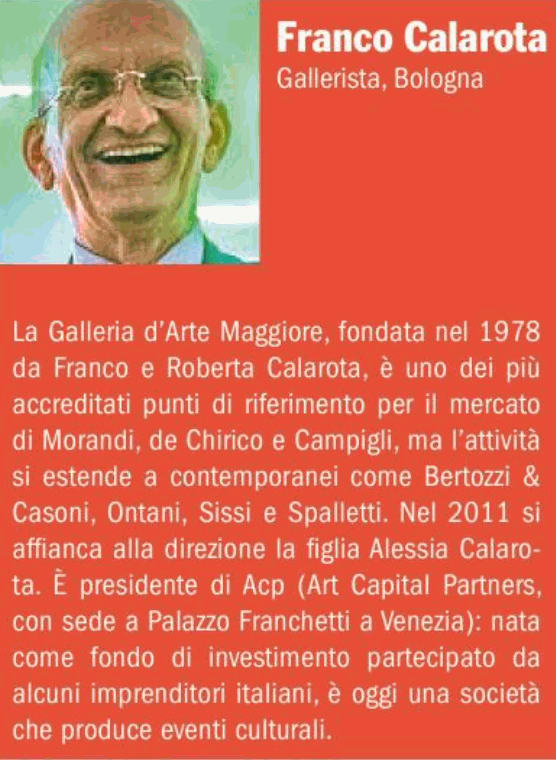

Once again, our research focuses on the Italian context. The list results from a comparative analysis of the names gathered—through countless consultations and recommendations by trusted professionals—by six contributors to this publication (Camilla Bertoni, Laura Lombardi, Ada Masoero, Francesca Romana Morelli, Michela Moro, and Olga Scotto di Vettimo), ensuring even geographic coverage of the investigation.

Readers will notice that auction houses are not included this time. That’s because all of them—Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Finarte, Il Ponte, Blindarte, Farsetti, Dorotheum, Bertolami, Pandolfini, Wannenes, Cambi, Meeting Art, Bolaffi—deserved to be mentioned. Each, in different ways, plays a significant role in this vast sector, especially because they reach every level and taste of collectors. To select some and exclude others would have been unfair.

One notable finding: the female presence in this list has noticeably declined compared to the previous edition. This reveals just how quickly and profoundly the Italian art system has changed over the past thirty years—a system once dominated by men (with rare exceptions).

A final reflection concerns the very concept of “Power”, as in the title of this list. Because we need to understand that we’re not only talking about economic or political power (in the broad sense). Throughout the consultations leading up to the creation of this list, we also considered another form of power: one better translated as authority or influence. A trait not only of conscientious critics and historians or serious and competent market operators, but also of those who lived through those pivotal art periods—as protagonists, witnesses, supporters, inspirers, creators, or promoters. Historical memory itself grants authority.

This is why, among the hundred names, many—gallery owners, critics, collectors, artists—remain indispensable points of reference, irreplaceable sources for establishing historical truth.

Just like in Fitzcarraldo, the film by Werner Herzog, when investors and businessmen—wanting to benefit from his doomed adventure—asked what proof he had for his story, the romantic adventurer who dreamed of bringing the opera house to the Amazon jungle replied:

“The proof is in my eyes, in my memory. My proof is my presence.”