"A new air has flooded my soul – I have heard a new song – and the whole world now seems completely transformed to me – the autumn afternoon has arrived – the long shadows, the clear air, the cheerful sky – in a word, Zarathustra has arrived, do you understand me?" Thus, in these sibylline terms, in January 1911, Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978) described to his friend Fritz Gartz the advent of the "metaphysical" phase of his art.

This metaphysics is the fruit of a particular sensibility, composed of dissatisfaction with reality, nostalgia for childhood and for the mythical origins of humanity, and a good measure of melancholy accompanied by the classic intestinal troubles. It is also the result of a reflection nourished by intense reading (Weininger, Schopenhauer, and above all Nietzsche). In 1910, re-reading Nietzsche profoundly shook the young painter—especially the idea, borrowed from Heraclitus, that the real world is not the one ordinarily perceived, that it is animated by occult forces whose meaning is revealed through mysterious signs. The works of the previous period were heavily indebted to the Symbolist aesthetic of Arnold Böcklin. During his stay in Munich, from 1905 to 1910, de Chirico was indeed deeply marked by the painting of Böcklin as well as that of Max Klinger. Both offered him the example of a painting in which mythological figures move within the framework of contemporary life, an art in which the present coexists with the mythical past. This vision responded to the artist’s own aspirations, as he lived his personal history through the myths that had nourished his childhood. Descended from an old Dalmatian family long established in Constantinople, De Chirico spent his youth in Greece. He was born in Volos, Thessaly, and studied in Athens. His childhood unfolded in a cultivated family (his father was a railway engineer) and in a world where ancient myths were vividly alive. Volos is the ancient Iolcos, the city from which the Argonauts set out to conquer the Golden Fleece. Nearby rises Mount Pelion, where Achilles was taught by the centaur Chiron. Giorgio and his brother Andrea (who would become a writer, composer, and painter under the name Alberto Savinio) nicknamed themselves the Dioscuri. The premature death of their father in 1905 and their departure for Munich marked the end of an era that the two brothers would never cease to reinterpret through the lens of mythological symbols.

The year 1910 was crucial: the artist left Bavaria for Italy—Milan, Rome, Florence, Turin. The re-reading of Nietzsche and the famous "revelation" of Florence were the source of a sudden crystallization of his intuitions, expressed in a series of paintings inaugurating the metaphysical period. "One clear autumn afternoon, I was sitting on a bench in Piazza Santa Croce. It was obviously not the first time I had seen this square. I had recently overcome a long and painful intestinal illness and found myself in a state of almost morbid sensitivity to light and noise. The whole world around me, even the marble of the buildings and fountains, seemed convalescent... The autumn sun, warm and loveless, lit up the statue and the façade of the church. I then had the strange impression that I was seeing these things for the first time, and the composition of my painting came to mind... Nevertheless, this moment is an enigma to me, for it is inexplicable."

This experience, lived as a "revelation," was at once a kind of projection of the ailing self onto the surrounding world and a dissociation of being from a reality perceived as foreign to oneself. The term "metaphysical" refers to Nietzsche’s notion of an art that would be "the supreme task and the truly metaphysical activity of this life" (The Birth of Tragedy). But the philosopher had proclaimed "the death of God," and this new metaphysics refers to no "beyond," no ideal or ultimate truth. The mysteries of existence must be sought in reality itself, within things, through the signs they contain as so many enigmas. "Schopenhauer and Nietzsche were the first to teach the profound meaning of the nonsense of life. They also taught how this nonsense can be converted into art," the painter would later write. The metaphysics of Giorgio de Chirico would be a painting of mourning: the mourning of a world now deprived of meaning; the mourning of the father, the great man, worthy representative of the civilization of progress; the mourning of a childhood perceived as fabulous. But this mourning was magnified by poetic illumination.

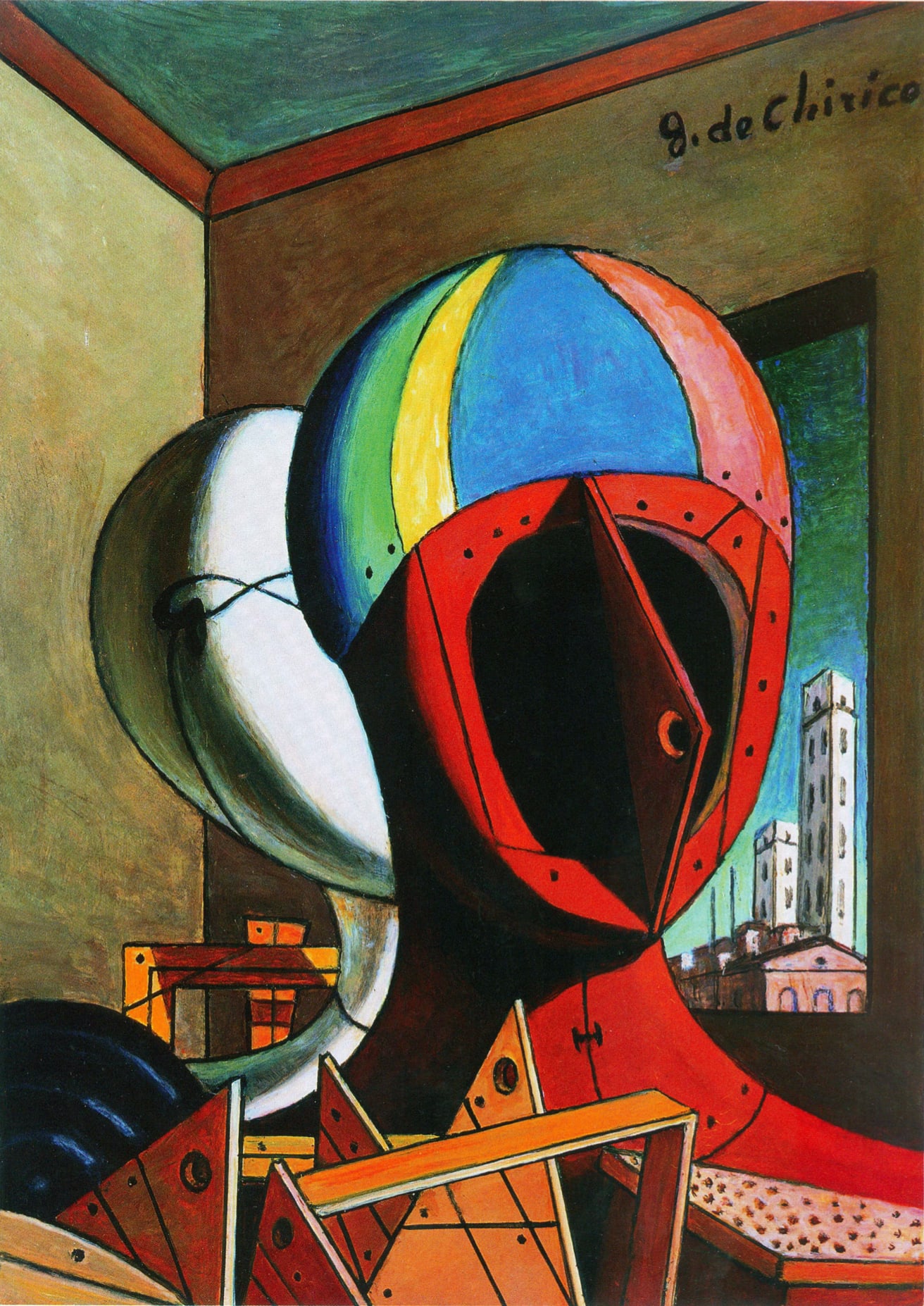

The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon, The Enigma of Arrival, The Enigma of the Hour, Solitude (Melancholy)... The works painted in Italy and later in Paris between 1911 and 1915 are the great icons of metaphysical painting. They depict architectures inspired by ancient or neoclassical buildings and by the great quadrangular squares of Turin, characterized by their succession of arcades full of shadow. Statues of great men or of a sleeping Ariadne rise on deserted plazas where, at times, a tiny silhouette wanders, intensely solitary. The cast shadows, elongated as in a late autumn afternoon, are dense, more concrete than the things themselves. Under the luminous sky, they create a kind of solar night. Behind the walls that block the horizon appear the sails of a ship, soon replaced by trains—references to the father, symbols of the artist-Argonaut’s initiatory journey. Train station clocks mark improbable, useless hours. Dislocated perspectives accumulate divergent viewpoints. Theater of an absence, these fascinating settings juxtapose solitary signs (detached from the logical or ideal chains of interpretation of reality) which thus function as enigmas. These signs may be incongruous, out-of-scale objects, such as the giant rubber glove and Apollo mask in The Song of Love (1914). In the paintings made in Ferrara during the First World War, the most disparate objects are piled into confined spaces: Metaphysical Interiorsadding claustrophobic unease to the tension of the enigma. New figures appear—faceless mannequins whose bodies are composed of objects, statuary fragments, rulers, rollers, squares, emblems of knowledge recalling the intricate paraphernalia of Dürer’s Melancholia.

Discovered in Paris and defended by Apollinaire, De Chirico’s metaphysical painting dazzled the Surrealists, who never forgave the artist for his later evolution. In 1919, before a painting by Titian, De Chirico had the "revelation of great painting." From then on, he converted to a neoclassical (later neo-romantic, neo-baroque) style, exalting the values of craftsmanship and traditional iconography. "Pictor classicus sum" became his new motto. It marked the beginning of a new career that would bring him success but would generally be scorned by critics. While it is impossible to judge in its entirety this long (more than half a century) and varied production—which, as Giovanni Lista suggests, might foreshadow the painting of the postmodern age—it is nonetheless difficult to deny this evidence: the radical originality, the high inspiration of the metaphysical period have vanished, replaced by systematic self-citation and self-celebration, by a painful complacency and narcissistic obsession illustrated in particular by pompous self-portraits, such as the so-called Self-portrait with Palette of 1924, bearing the inscription "Eternal glory will be granted to me." In Latin, of course.

The masks. 1973, oil on canvas. 25 x 18 cm (private collection, M.B. Courtesy Galleria d'Arte Maggiore, Bologna)