""I wanted to do away with the notion that figuration had to be romantic and couldn't be tough.""

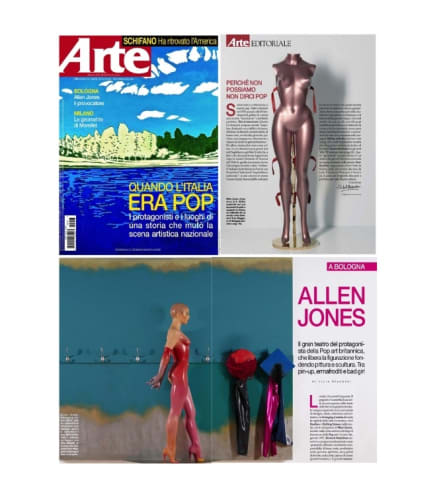

London, late 1950s. The greyness and austerity of a city still marked by the wounds of World War II are swept away by a wave of energy, color, optimism, and hedonism. Swinging London becomes the capital of style: in music, with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, in fashion, with Mary Quant's miniskirts, while on the artistic scene, the phenomenon of Pop art bursts onto the scene. An art that, as early as 1957, Richard Hamilton programmatically described as "popular, ephemeral, easily understandable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, full of discoveries, seductive, capable of creating great business." And great scandal. Among the group of British pop artists, alongside Richard Hamilton, R. B. Kitaj, Peter Blake, Peter Phillips, Derek Boshiere, and David Hockney, the most scandalous, the most provocative of all is undoubtedly Allen Jones (Southampton, 1937). In 1970, when his Hatstand, Table, and Chair (1969) were first exhibited, they enraged feminists (and not only them) who saw in them the objectified woman turned into sculpture. Hatstand (coat stand) is a female figure made of fiberglass, resembling a mannequin, with an expressionless face, dressed in fetish attire (the black leather was made by the same company that created Diana Rigg's suit in the TV series The Avengers) and displayed standing with arms ready to hold coats and hats; the second mannequin, "on all fours," with a glass panel on its back becomes a table (Table), while the third mannequin, supine, with knees folded against the chest and a cushion on top, serves as a chair (Chair). In short, the woman, totally depersonalized, is presented as a piece of furniture, a mundane consumer object.

AMERICAN GRAND TOUR.

The idea of these women-furniture came to him during a stay in the United States. After studying engraving and painting at the Hornsey College of Art in London and being expelled from the Royal College of Art in 1960, in 1964 Allen Jones moved to New York and, along with his friend Peter Phillips and other artists who were questioning the academic approach of English painting, he opened a studio in the famous Chelsea Hotel. The following year, still with Phillips, he embarked on a road trip through provincial America to immerse himself in the consumerist universe and assimilate the new pop aesthetic. Entering a casino in Las Vegas, the revelation struck Jones: he encountered a slot machine "transplanted" into the form of a pin-up. Convinced that contemporary art and mass entertainment shared the same roots, the artist began to represent new sexual freedoms with cynical absurdity, drawing from commercial imagery, pornographic magazines, comics, and advertising: "I wanted to push the limits of what was considered acceptable in the artistic field, invent a new language, and put an end to the idea that figuration was 'romantic' and couldn't be 'tough'," he recounts. "The furniture-sculptures were born from the belief that figuration still had something to say in the context of the avant-garde of the 1960s, despite the prevailing thought (postulated by the MoMA) that Modernist art went from Mondrian to Minimalism. I was friends with many minimalist artists and loved their work, but the idea that after 40,000 years figurative art should come to an end because of Donald Judd's empty boxes was simply ridiculous." Jones's ironic "furniture" provoked as much outrage (in 1978 Chair, exhibited at the Tate in London, was vandalized with acid) as enthusiasm: in 1971 director Stanley Kubrick asked Jones to create some works to furnish the Korova Milk Bar in the film A Clockwork Orange (upon his refusal, Kubrick had imitations made), and Allen Jones's works soon became part of the collections of Roman Polanski, Elton John, and Gunter Sachs. In 2012, Hatstand, Table, and Chair, from the collection of the German photographer and playboy, husband of Brigitte Bardot, were auctioned as separate lots by Sotheby's London for a total value of over 3 million and 200 thousand euros.

PAINTER WHO SCULPTS.

Despite having established himself on the international scene with sculpture-furniture, Allen Jones considers himself, deep down, a painter: "I am a painter who sculpts," he says of himself. Testifying to his great expressive freedom and inventiveness is the exhibition Forever Icon, open until April 14th at the Galleria d'Arte Maggiore in Bologna, where the artist had already exhibited in 1999 and 2002. Various works are brought together, blending painting and sculpture, representing the attempt to "free" painting from the frame of the canvas or, conversely, to "bring in" sculpture into the painting (Changing room, 2016). In addition to the female figures that have dominated his universe since the 1960s, there are also strongly stylized male figures, which in the painted steel sculptures are often rendered through few elements such as the hat, tie, and dark suit (Untitled man, 1989, Man losing his head and hat, 1988). The setting always includes some allusion to the world of theater: often surrounded by curtains, mirrors, masks, the figures stride elegantly like models in a fashion show (Backdrop, 2016-2017), watch a show from a box (Bravo!, 2017), or dance on a stage locked in an embrace: it is the dance of life that merges man and woman with saturated colors (Semi Quiver, 1997, Crescendo, 2003). Everything is in motion, everything is color in his works, which offer a reflection on the mechanisms of attraction between man and woman. Bodies merge until they become one, surpassing the distinction between genders: hermaphroditism is a theme that has fascinated Jones since the works of the 1970s. The exhibition also includes a work dedicated to Kate Moss, previously exhibited in Allen Jones's retrospective at the Royal Academy in London (2014). The armor worn by the model was created by the artist in 1974 for a film: "It was the story of a girl who wanted to become a model. But she had a problem: every time she stood under the spotlights, she turned into a man. Her boyfriend, an artist, managed to save her by creating an armor dress that enveloped her, preserving her identity as a woman." The film was never made, but when, in 2013, Christie's commissioned him a work for an exhibition on Kate Moss, Jones decided to portray Kate with the golden armor: a way to forever fix her icon as the eternal bad girl.